103 KiB

Data Science for the Linear Algebraist.

Project Overview

A not-so comprehensive guide bridging linear algebra theory with practical data science implementation. Meant for someone to learn data science by using their strong linear algebra background. This project demonstrates how fundamental linear algebra concepts power modern machine learning algorithms, with hands-on Python implementations.

Main Dependencies

- Python 3

- NumPy - Matrix operations and linear algebra

- Pandas - Data manipulation

- Matplotlib - Visualization

Key Demonstrations

- Least Squares Regression - From theory to implementation

- QR Decomposition and SVD - Numerical stability in solving systems

- PCA - Dimensionality reduction

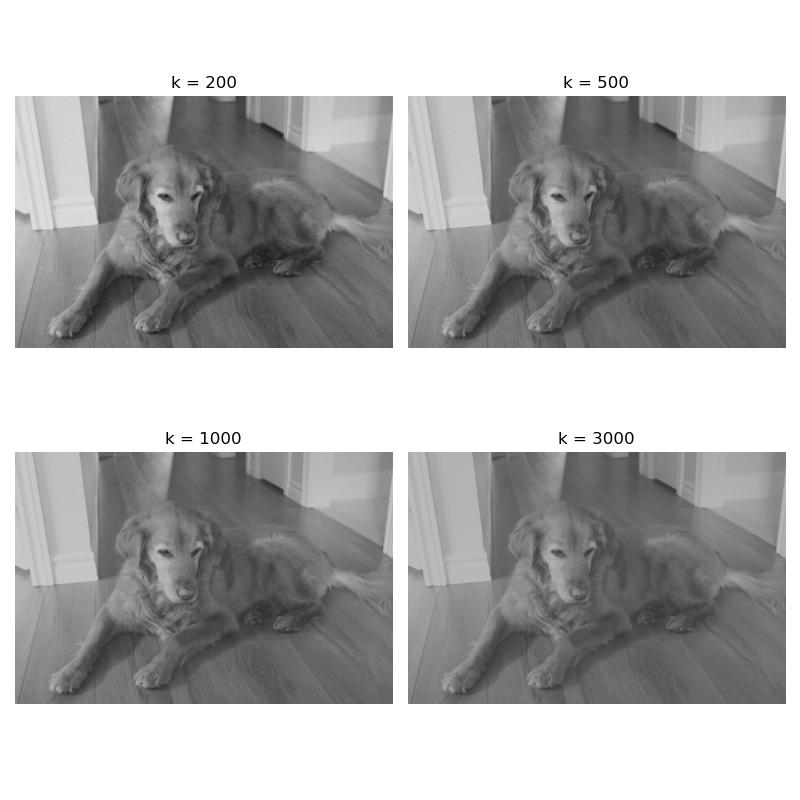

- Project - Applying low-rank approximation (via truncated SVD) to an image of my beautiful dog

To do

- Upload Jupyter notebook

Contact

Pawel Sarkowicz

🌐 website

💻 git

January 2026

Table of Contents

- Introduction: The Basic Data Science Problem

- Solving the Problem: Least Squares and Matrix Decompositions

- Principal Component Analysis

- Project: Spectral Image Denoising via Truncated SVD

- Appendix

- Bibliography

Introduction

This is meant to be a not entirely comprehensive introduction to Data Science for the Linear Algebraist. There are of course many other complicated topics, but this is just to get the essence of data science (and the tools involved) from the perspective of someone with a strong linear algebra background.

One of the most fundamental questions of data science is the following.

Question: Given observed data, how can we predict certain targets?

The answer of course boils down to linear algebra, and we will begin by translating data science terms and concepts into linear algebraic ones. But first, as should be common practice for the linear algebraist, an example.

Example. Suppose that we observe

n=3houses, and for each house we record

- the square footage,

- the number of bedrooms,

- and additionally the sale price.

So we have a table as follows.

House Square ft Bedrooms Price (in $1000s) 0 1600 3 500 1 2100 4 650 2 1550 2 475 So, for example, the first house is 1600 square feet, has 3 bedrooms, and costs $500,000, and so on. Our goal will be to understand the cost of a house in terms of the number of bedrooms as well as the square footage. Concretely this gives us a matrix and a vector:

X = \begin{bmatrix} 1600 & 3 \\ 2100 & 4 \\ 1550 & 2 \end{bmatrix} \text{ and } y =\begin{bmatrix} 500 \\ 650 \\ 475 \end{bmatrix}So translating to linear algebra, the goal is to understand how

ydepends on the columns ofX.

Translation from Data Science to Linear Algebra

| Data Science (DS) Term | Linear Algebra (LA) Equivalent | Explanation |

|---|---|---|

| Dataset (with (n) observations and (p) features) | A matrix X \in \mathbb{R}^{n \times p} |

The dataset is just a matrix. Each row is an observation (a vector of features). Each column is a feature (a vector of its values across all observations). |

| Features | Columns of X |

Each feature is a column in your data matrix. |

| Observation | Rows of X |

Each data point corresponds to a row. |

| Targets | A vector y \in \mathbb{R}^{n \times 1} |

The list of all target values is a column vector. |

| Model parameters | A vector \beta \in \mathbb{R}^{p \times 1} |

These are the unknown coefficients. |

| Model | Matrix–vector equation | The relationship becomes an equation involving matrices and vectors. |

| Prediction Error / Residuals | A residual vector e \in \mathbb{R}^{n \times 1} |

Difference between actual targets and predictions. |

| Training / "best fit" | Optimization: minimizing the norm of the residual vector | To find the "best" model by finding a model which makes the norm of the residual vector as small as possible. |

So our matrix X will represent our data set, our vector y is the target, and \beta is our vector of parameters. We will often be interested in understanding data with "intercepts", i.e., when there is a base value given in our data. So we will augment a column of 1's (denoted by \mathbb 1) to X and append a parameter \beta_0 to the top of \beta, yielding

\tilde{X} = \begin{bmatrix} \mathbb{1} & X \end{bmatrix} \text{ and } \tilde{\beta} = \begin{bmatrix} \beta_0 \\ \beta_1 \\ \beta_2 \\ \vdots \\ \beta_p \end{bmatrix}.

So the answer to the Data Science problem becomes

Answer: Solve, or best approximate a solution to, the matrix equation

\tilde{X}\tilde{\beta} = y.

To be explicit, given \tilde{X} and y, we want to find a \tilde{\beta} that does a good job of roughly giving \tilde{X}\tilde{\beta} = y. There of course ways to solve (or approximate) such small systems by hand. However, one will often be dealing with enormous data sets with plenty to be desired. One view to take is that modern data science is applying numerical linear algebra techniques to imperfect information, all to get as good a solution as possible.

Solving the problem: Least Squares Regression and Matrix Decompositions

If the system \tilde{X}\tilde{\beta} = y is consistent, then we can find a solution. However, we are often dealing with overdetermined systems, in the sense that there are often more observations than features (i.e., more rows than columns in \tilde{X}, or more equations than unknowns), and therefore inconsistent systems. However, it is possible to find a best fit solution, in the sense that the difference

e = y - \tilde{X}\tilde{\beta}

is small. By small, we often mean that e is small in L^2 norm; i.e., we are minimizing the the sums of the squares of the differences between the components of y and the components of \tilde{X}\tilde{\beta}. This is known as a least squares solution. Assuming that our data points live in the Euclidean plane, this precisely describes finding a line of best fit.

The structure of this sections is as follows.

- Least Squares Solution

- QR Decompositions

- Singular Value Decomposition

- A note on other norms

- A note on regularization

- A note on solving multiple targets concurrently

- Polynomial regression

- What can go wrong?

Least Squares Solution

Recall that the Euclidean distance between two vectors x = (x_1,\dots,x_n) ,y = (y_1,\dots,y_n) \in \mathbb{R}^n is given by

||x - y||_2 = \sqrt{\sum_{i=1}^n |x_i - y_i|^2}.

We will often work with the square of the L^2 norm to simplify things (the square function is increasing, so minimizing the square of a non-negative function will also minimize the function itself).

Definition: Let

Abe anm \times nmatrix andb \in \mathbb{R}^n. A least-squares solution ofAx = bis a vectorx_0 \in \mathbb{R}^nsuch that\|b - Ax_0\|_2 \leq \|b - Ax\|_2 \text{ for all } x \in \mathbb{R}^n.

So a least-squares solution to the equation Ax = b is trying to find a vector x_0 \in \mathbb{R}^n which realizes the smallest distance between the vector b and the column space

\text{Col}(A) = \{Ax \mid x \in \mathbb{R}^n\}

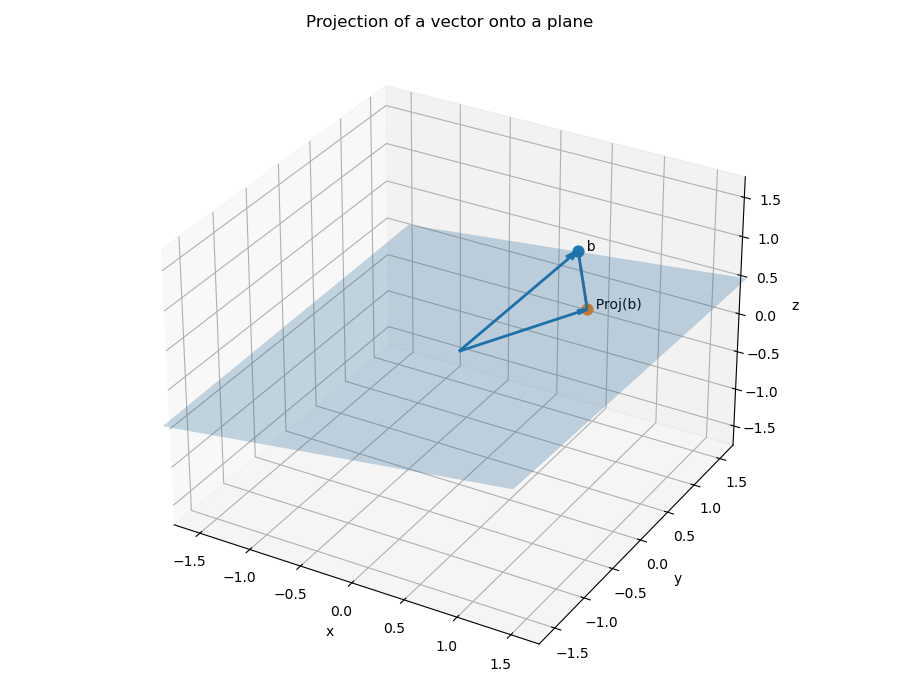

of A. We know this to be the projection of the vector b onto the column space.

Theorem: The set of least-squares solutions of

Ax = bcoincides with solutions of the normal equationsA^TAx = A^Tb. Moreover, the normal equations always have a solution.

Let us first see why we get a line of best fit.

Example. Let us show why this describes a line of best fit when we are working with one feature and one target. Suppose that we observe four data points

X = \begin{bmatrix} 1 \\ 2 \\ 3 \\ 4 \end{bmatrix} \text{ and } y = \begin{bmatrix} 1 \\ 2\\ 2 \\ 4 \end{bmatrix}.We want to fit a line

y = \beta_0 + \beta_1xto these data points. We will have our augmented matrix be\tilde{X} = \begin{bmatrix} 1 & 1 \\ 1 & 2 \\ 1 & 3 \\ 1 & 4 \end{bmatrix},and our parameter be

\tilde{\beta} = \begin{bmatrix} \beta_0 \\ \beta_1 \end{bmatrix}.We have that

\tilde{X}^T\tilde{X} = \begin{bmatrix} 4 & 10 \\ 10 & 30 \end{bmatrix} \text{ and } \tilde{X}^Ty = \begin{bmatrix} 9 \\ 27 \end{bmatrix}.The 2x2 matrix

\tilde{X}^T\tilde{X}is easy to invert, and so we get that\tilde{\beta} = (\tilde{X}^T\tilde{X})^{-1}\tilde{X}^Ty = \frac{1}{10}\begin{bmatrix} 15 & -5 \\ -5 & 2 \end{bmatrix}\begin{bmatrix} 9 \\ 27 \end{bmatrix} = \begin{bmatrix} 0 \\ \frac{9}{10} \end{bmatrix}.So our line of best fit is of them form

y = \frac{9}{10}x.

Although the above system was small and we could solve the system of equations explicitly, this isn't always feasible. We will generally use python in order to solve large systems.

- One can find a least-squares solution using

numpy.linalg.lstsq. - We can set up the normal equations and solve the system by using

numpy.linalg.solveAlthough the first approach simplifies things greatly, and is more or less what we are doing anyway, we will generally set up our problems as we would by hand, and then usenumpy.linalg.solveto help us find a solution. However, computingX^TXcan cause lots of errors, so later we'll see how to get linear systems from QR decompositions and the SVD, and then applynumpy.lingalg.solve.

Let's see how to use these for the above example, and see the code to generate the scatter plot and line of best fit. Again, our system is the following.

X = \begin{bmatrix} 1 \\ 2 \\ 3 \\ 4 \end{bmatrix} \text{ and } y = \begin{bmatrix} 1 \\ 2\\ 2 \\ 4 \end{bmatrix}.

We will do what we did above, but use python instead.

import numpy as np

# Define the matrix X and vector y

X = np.array([[1], [2], [3], [4]])

y = np.array([[1], [2], [2], [4]])

# Augment X with a column of 1's (intercept)

X_aug = np.hstack((np.ones((X.shape[0], 1)), X))

# Solve the normal equations

beta = np.linalg.solve(X_aug.T @ X_aug, X_aug.T @ y)

And what is the result?

>>> beta

array([[-1.0658141e-15],

[ 9.0000000e-01]])

This agrees with our by-hand computation: the intercept is tiny, so it is virtually zero, and we get 9/10 as our slope. Let's plot it.

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

b, m = beta #beta[0] will be the intercept and beta[1] will be the slope

_ = plt.plot(X, y, 'o', label='Original data', markersize=10)

_ = plt.plot(X, m*X + b, 'r', label='Line of best fit')

_ = plt.legend()

plt.show()

What about numpy.linalg.lstsq? Is it any different?

import numpy as np

# Define the matrix X and vector y

X = np.array([[1], [2], [3], [4]])

y = np.array([[1], [2], [2], [4]])

# Augment X with a column of 1's (intercept)

X_aug = np.hstack((np.ones((X.shape[0], 1)), X))

# Solve the least squares equation with matrix X_aug and target y

beta = np.linalg.lstsq(X_aug,y)[0]

We then get

>>> beta

array([[6.16291085e-16],

[9.00000000e-01]])

So it is a little different -- and, in fact, closer to our exact answer (the intercept is zero). This makes sense -- numpy.linalg.lstsq won't directly compute X^TX, which, again, can cause quite a few issues.

Now going to our initial example.

Example: Let us work with the example from above. We augment the matrix with a column of 1's to include an intercept term:

\tilde{X} = \begin{bmatrix} 1 & 1600 & 3 \\ 1 & 2100 & 4 \\ 1 & 1550 & 2 \end{bmatrix}.Let us solve the normal equations

\tilde{X}^T\tilde{X}\tilde{\beta} = \tilde{X}^Ty.We have

\tilde{X}^T\tilde{X} = \begin{bmatrix} 3 & 5250 & 9 \\ 5250 & 9372500 & 16300 \\ 9 & 16300 & 29\end{bmatrix} \text{ and } \tilde{X}^Ty = \begin{bmatrix} 1625 \\ 2901500 \\ 5050 \end{bmatrix}Solving this system of equations yields the parameter vector

\tilde{\beta}. In this case, we have\tilde{\beta} = \begin{bmatrix} \frac{200}{9} \\ \frac{5}{18} \\ \frac{100}{9} \end{bmatrix}.When we apply

\tilde{X}to\tilde{\beta}, we get\tilde{X}\tilde{\beta} = \begin{bmatrix} 500 \\ 650 \\ 475 \end{bmatrix},which is our target on the nose. This means that we can expect, based on our data, that the cost of a house will be

\frac{200}{9} + \frac{5}{18}(\text{square footage}) + \frac{100}{9}(\text{\# of bedrooms})

In the above, we actually had a consistent system to begin with, so our least-squares solution gave our prediction honestly. What happens if we have an inconsistent system?

Example: Let us add two more observations, say our data is now the following.

House Square ft Bedrooms Price (in $1000s) 0 1600 3 500 1 2100 4 650 2 1550 2 475 3 1600 3 490 4 2000 4 620 So setting up our system, we want a least-square solution to the matrix equation

\begin{bmatrix} 1 & 1600 & 3 \\ 1 & 2100 & 4 \\ 1 & 1550 & 2 \\ 1 & 1600 & 3 \\ 1 & 2000 & 4 \end{bmatrix}\tilde{\beta} = \begin{bmatrix} 500 \\ 650 \\ 475 \\ 490 \\ 620 \end{bmatrix}.Note that the system is inconsistent (the 1st and 4th rows agree in

\tilde{X}, but they have different costs). Writing the normal equations we have\tilde{X}^T\tilde{X} = \begin{bmatrix} 5 & 8850 & 16 \\ 8850 & 15932500 & 29100 \\ 16 & 29100 & 54 \end{bmatrix} \text{ and } \tilde{X}y = \begin{bmatrix} 2735 \\ 4 925 250 \\ 9000 \end{bmatrix}.Solving this linear system yields

\tilde{\beta} = \begin{bmatrix} 0 \\ \frac{3}{10} \\ 5 \end{bmatrix}.This is a vastly different answer! Applying

\tilde{X}to it yields\tilde{X}\tilde{\beta} = \begin{bmatrix} 495 \\ 650 \\ 475 \\ 495 \\ 620 \end{bmatrix}.Note that the error here is

y - \tilde{X}\tilde{\beta} = \begin{bmatrix} 5 \\ 0 \\ 0 \\ -5 \\ 0 \end{bmatrix},which has squared

L^2norm\|y - \tilde{X}\tilde{\beta}\|_2^2 = 25 + 25 = 50.So this says that, given our data, we can roughly estimate the cost of a house, within 50k or so, to be

\approx \frac{3}{10}(\text{square footage}) + 5(\text{\# of bedrooms}).

In practice, our data sets can be gigantic, and so there is absolutely no hope of doing computations by hand. It is nice to know that theoretically we can do things like this though.

Theorem: Let

Abe anm \times nmatrix andb \in \mathbb{R}^n. The following are equivalent.

- The equation

Ax = bhas a unique least-squares solution for eachb \in \mathbb{R}^n.- The columns of

Aare linearly independent.- The matrix

A^TAis invertible.

In this case, the unique solution to the normal equations A^TAx = A^Tb is

x_0 = (A^TA)^{-1}A^Tb.

Computing \tilde{X}^T\tilde{X} or taking inverses are very computationally intensive tasks, and it is best to avoid doing these. Moreover, as we'll see in an example later, if we do a numerical calculation we can get close to zero and then divide where we shouldn't be, blowing up our final result. One way to get around this is to use QR decompositions of matrices.

Now let's use python to visualize the above data and then solve for the least-squares solution. We'll use pandas in order to think about this data. We note that pandas incorporates matplotlib under the hood already, so there are some simplifications that can be made.

import numpy as np

import pandas as pd

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

# First let us make a dictionary incorporating our data.

# Each entry corresponds to a column (feature of our data)

data = {

'Square ft': [1600, 2100, 1550, 1600, 2000],

'Bedrooms': [3, 4, 2, 3, 4],

'Price': [500, 650, 475, 490, 620]

}

# Create a pandas DataFrame

df = pd.DataFrame(data)

Let's see how python formats this DataFrame. It will turn it into essentially the table we had at the beginning.

>>> df

Square ft Bedrooms Price

0 1600 3 500

1 2100 4 650

2 1550 2 475

3 1600 3 490

4 2000 4 620

So what can we do with DataFrames? First let's use pandas.DataFrame.describe to see some basic statistics about our data.

>>> df.describe()

Square ft Bedrooms Price

count 5.000000 5.00000 5.000000

mean 1770.000000 3.20000 547.000000

std 258.843582 0.83666 81.516869

min 1550.000000 2.00000 475.000000

25% 1600.000000 3.00000 490.000000

50% 1600.000000 3.00000 500.000000

75% 2000.000000 4.00000 620.000000

max 2100.000000 4.00000 650.000000

This gives use the mean, the standard deviation, the min, the max, as well as some other things. We get an immediate sense of scale from our data. We can also examine the pairwise correlation of all the columns by using pandas.DataFrame.corr.

>>> df[["Square ft", "Bedrooms", "Price"]].corr()

Square ft Bedrooms Price

Square ft 1.000000 0.900426 0.998810

Bedrooms 0.900426 1.000000 0.909066

Price 0.998810 0.909066 1.000000

It is clear that each of the three are correlated. This makes sense, as the number of bedrooms should be increasing with the square feet. Same with the price. We'll discuss in the next section when we look at Principal Component Analysis.

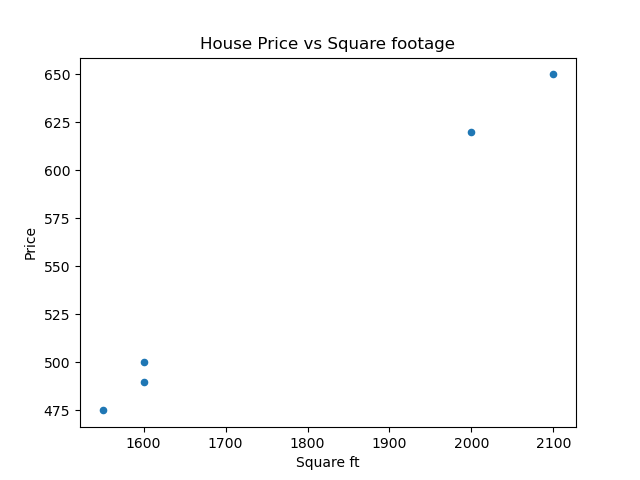

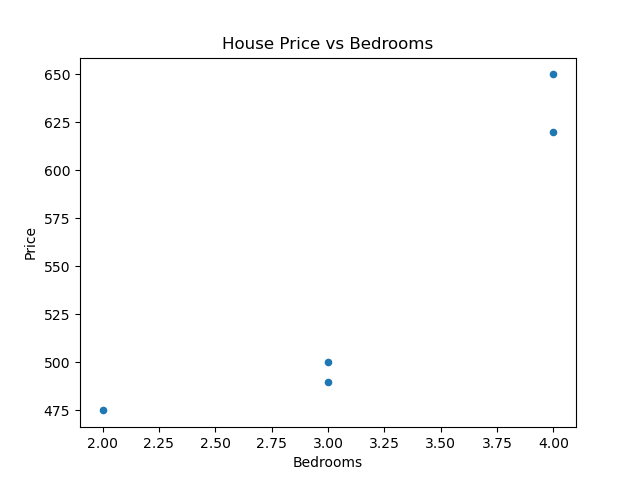

We can also graph our data; for example, we could create some scatter plots, one for Square ft vs Price and on for Bedrooms vs Price. We can also do a grouped bar chart. Let's start with the scatter plots.

# Scatter plot for Price vs Square ft

df.plot(

kind="scatter",

x="Square ft",

y="Price",

title="House Price vs Square footage"

)

plt.show()

# Scatter plot for Price vs Bedrooms

df.plot(

kind="scatter",

x="Bedrooms",

y="Price",

title="House Price vs Bedrooms"

)

plt.show()

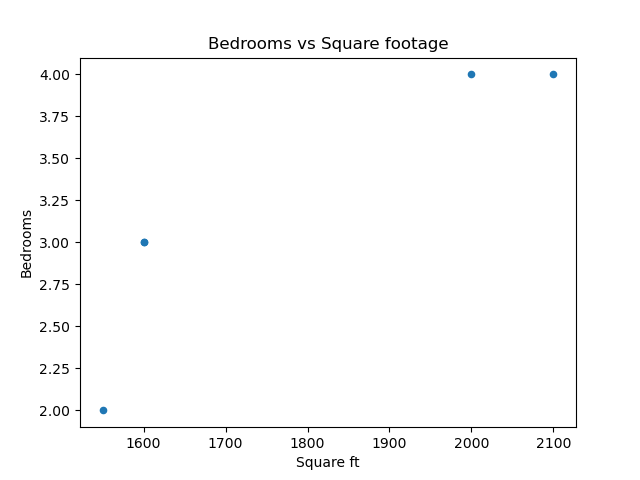

We can even do square footage vs bedrooms.

# Scatter plot for Bedrooms vs Square ft

df.plot(

kind="scatter",

x="Square ft",

y="Bedrooms",

title="Bedrooms vs Square footage"

)

plt.show()

Of course, these figures are somewhat meaningless due to how unpopulated our data is.

Now let's get our matrices and linear systems set up with pandas.DataFrame.to_numpy.

# Create our matrix X and our target y

X = df[["Square ft", "Bedrooms"]].to_numpy()

y = df[["Price"]].to_numpy()

# Augment X with a column of 1's (intercept)

X_aug = np.hstack((np.ones((X.shape[0], 1)), X))

# Solve the least-squares problem

beta = np.linalg.lstsq(X_aug,y)[0]

This yields

>>> beta

array([[4.0098513e-13],

[3.0000000e-01],

[5.0000000e+00]])

As the first parameter is basically 0, we are left with the second being 3/10 and the third being 5, just like our exact solution. Next, we will look at matrix decompositions and how they can help us find least-squares solutions.

QR Decompositions

QR decompositions are a powerful tool in linear algebra and data science for several reasons. They provide a way to decompose a matrix into an orthogonal matrix Q aand an upper triangular matrix R, which can simplify many computations and analyses.

Theorem: Let

Ais anm \times nmatrix with linearly independent columns (m \geq nin this case), thenAcan be decomposed asA = QRwhereQis anm \times nmatrix whose columns form an orthonormal basis for Col(A) andRis ann \times nupper-triangular invertible matrix with positive entries on the diagonal.

In the literature, sometimes the QR decomposition is phrased as follows: any m \times n matrix A can also be written as A = QR where Q is an m \times m orthogonal matrix (Q^T = Q^{-1}), and R is an m \times n upper-triangular matrix. One follows from the other by playing around with some matrix equations. Indeed, suppose that A = Q_1R_1 is a decomposition as above (that is, Q_1 is m \times n and R_1 is n \times n). Use can use the Gram-Schmidt procedure to extend the columns of Q_1 to an orthonormal basis for all of \mathbb{R}^m, and put the remaining vectors in a (m - n) \times n matrix Q_2. Then

A = Q_1R_1 = \begin{bmatrix} Q_1 & Q_2 \end{bmatrix}\begin{bmatrix} R_1 \\ 0 \end{bmatrix}.

The left matrix is an m \times m orthogonal matrix and the right matrix is m \times n upper triangular. Moreover, the decomposition provides orthonormal bases for both the column space of A and the perp of the column space of A; Q_1 will consist of an orthonormal basis for the column space of A and Q_2 will consist of an orthonormal basis for the perp of the column space of A.

However, we will often want to use the decomposition when Q is m \times n, R is n \times n, and the columns of Q form an orthonormal basis for the column space of A. For example, the python function numpy.linalg.qr give QR decompositions this way (again, assuming that the columns of A are linearly independent, so m \geq n).

Key take-away. The QR decomposition provides an orthonormal basis for the column space of

A. IfAhas rankk, then the firstkcolumns ofQwill form a basis for the column space ofA.

For small matrices, one can find Q and R by hand, assuming that A = [ a_1\ \cdots\ a_n ] has full column rank. Let e_1,\dots,e_n be the unnormalized vectors we get when we apply Gram-Schmidt to c_1,\dots,c_n, and let u_1,\dots,u_n be their normalizations. Let

r_j = \begin{bmatrix} \langle e_1,c_j \rangle \\ \vdots \\ \langle e_n, c_j \rangle \end{bmatrix},

and note that \langle e_i,c_j \rangle = 0 whenever i > j. Thus

Q = \begin{bmatrix} u_1 & \cdots & u_n \end{bmatrix} \text{ and } R = \begin{bmatrix} r_1 & \cdots & r_n \end{bmatrix}

give rise to a A = QR, where the columns of Q form an orthonormal basis for \text{Col}(A) and R is upper-triangular. We can also compute R directly from Q and Q. Indeed, note that Q^TQ = I, so

Q^TA = Q^T(QR) = IR = R.

Example. Find a QR decomposition for the matrix

A = \begin{bmatrix} 1 & 1 & 1 \\ 0 & 1 & 1 \\ 0 & 0 & 1 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 \end{bmatrix}.Note that one trivially see (or by applying the Gram-Schmidt procedure) that

\begin{bmatrix} 1 \\ 0 \\ 0 \\ 0 \end{bmatrix}, \begin{bmatrix} 0 \\ 1 \\ 0 \\ 0 \end{bmatrix}, \begin{bmatrix} 0 \\ 0 \\ 1 \\ 0 \end{bmatrix}forms an orthonormal basis for the column space of

A. So withQ = \begin{bmatrix} 1 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 1 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 1 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 \end{bmatrix} \text{ and }R = \begin{bmatrix} 1 & 1 & 1\\ 0 & 1 & 1 \\ 0 & 0 & 1 \end{bmatrix},we have

A = QR.

Let's do a more involved example.

Example. Consider the matrix

A = \begin{bmatrix} 1 & 0 & 0 \\ 1 & 1 & 0 \\ 1 & 1 & 1 \\ 1 & 1 & 1 \end{bmatrix}.One can apply the Gram-Schmidt procedure to the columns of

Ato find that\begin{bmatrix} 1 \\ 1 \\ 1 \\ 1 \end{bmatrix}, \begin{bmatrix} -3 \\ 1 \\ 1 \\ 1 \end{bmatrix}, \begin{bmatrix} 0 \\ -\frac{2}{3} \\ \frac{1}{3} \\ \frac{1}{3}\end{bmatrix}forms an orthogonal basis for the column space of

A. Normalizing, we get thatQ = \begin{bmatrix} \frac{1}{2} & -\frac{3}{\sqrt{12}} & 0 \\ \frac{1}{2} & \frac{1}{\sqrt{12}} & -\frac{2}{\sqrt{6}} \\ \frac{1}{2} & \frac{1}{\sqrt{12}} & \frac{1}{\sqrt{6}} \\ \frac{1}{2} & \frac{1}{\sqrt{12}} & \frac{1}{\sqrt{6}} \end{bmatrix}is an appropriate

Q. Thus\begin{split} R = Q^TA &= \begin{bmatrix} \frac{1}{2} & \frac{1}{2} & \frac{1}{2} & \frac{1}{2} \\ -\frac{3}{\sqrt{12}} & \frac{1}{\sqrt{12}} & \frac{1}{\sqrt{12}} & \frac{1}{\sqrt{12}} \\ 0 & -\frac{2}{\sqrt{6}} & \frac{1}{\sqrt{6}} & \frac{1}{\sqrt{6}} \end{bmatrix}\begin{bmatrix} 1 & 0 & 0 \\ 1 & 1 & 0 \\ 1 & 1 & 1 \\ 1 & 1 & 1 \end{bmatrix} \\ &= \begin{bmatrix} 2 & \frac{3}{2} & 1 \\ 0 & \frac{3}{\sqrt{12}} & \frac{2}{\sqrt{12}} \\ 0 & 0 & \frac{2}{\sqrt{6}} \end{bmatrix}. \end{split}So all together,

A = \begin{bmatrix} \frac{1}{2} & -\frac{3}{\sqrt{12}} & 0 \\ \frac{1}{2} & \frac{1}{\sqrt{12}} & -\frac{2}{\sqrt{6}} \\ \frac{1}{2} & \frac{1}{\sqrt{12}} & \frac{1}{\sqrt{6}} \\ \frac{1}{2} & \frac{1}{\sqrt{12}} & \frac{1}{\sqrt{6}} \end{bmatrix}\begin{bmatrix} 2 & \frac{3}{2} & 1 \\ 0 & \frac{3}{\sqrt{12}} & \frac{2}{\sqrt{12}} \\ 0 & 0 & \frac{2}{\sqrt{6}} \end{bmatrix}.

To do this numerically, we can use numpy.linalg.qr.

# Define our matrices

A = np.array([[1,1,1],[0,1,1],[0,0,1],[0,0,0]])

B = np.array([[1,0,0],[1,1,0],[1,1,1],[1,1,1]])

# Take QR decompositions

QA, RA = np.linalg.qr(A)

QB, RB = np.linalg.qr(B)

Our resulting matrices are:

>>> QA

array([[ 1., 0., 0.],

[-0., 1., 0.],

[-0., -0., 1.],

[-0., -0., -0.]])

>>> RA

array([[1., 1., 1.],

[0., 1., 1.],

[0., 0., 1.]])

>>> QB

array([[-0.5 , 0.8660254 , 0. ],

[-0.5 , -0.28867513, 0.81649658],

[-0.5 , -0.28867513, -0.40824829],

[-0.5 , -0.28867513, -0.40824829]])

>>> RB

array([[-2. , -1.5 , -1. ],

[ 0. , -0.8660254 , -0.57735027],

[ 0. , 0. , -0.81649658]])

How to use QR decompositions

One of the primary uses of QR decompositions is to solve least squares problems, as introduced above. Assuming that A has full column rank, we can write A = QR as a QR decomposition, and then we can find a least-squares solution to Ax = b by solving the upper-triangular system.

Theorem. Let

Abe anm \times nmatrix with full column rank, and letA = QRbe a QR factorization ofA. Then, for eachb \in \mathbb{R}^m, the equationAx = bhas a unique least-squares solution, arising from the systemRx = Q^Tb.

Normal equations can be ill-conditioned, i.e., small errors in calculating A^TA give large errors when trying to solve the least-squares problem. When A has full column rank, a QR factorization will allow one to compute a solution to the least-squares problem more reliably.

Example. Let

A = \begin{bmatrix} 1 & 0 & 0 \\ 1 & 1 & 0 \\ 1 & 1 & 1 \\ 1 & 1 & 1 \end{bmatrix} \text{ and } b = \begin{bmatrix} 1 \\ 1 \\ 1 \\ 0 \end{bmatrix}.We can find the least-squares solution

Ax = bby using the QR decomposition. Let us use the QR decomposition from above, and solve the systemRx = Q^Tb.As

\begin{bmatrix} \frac{1}{2} & -\frac{3}{\sqrt{12}} & 0 \\ \frac{1}{2} & \frac{1}{\sqrt{12}} & -\frac{2}{\sqrt{6}} \\ \frac{1}{2} & \frac{1}{\sqrt{12}} & \frac{1}{\sqrt{6}} \\ \frac{1}{2} & \frac{1}{\sqrt{12}} & \frac{1}{\sqrt{6}} \end{bmatrix}^T\begin{bmatrix} 1 \\ 1 \\ 1 \\ 0 \end{bmatrix} = \begin{bmatrix} \frac{3}{2} \\ -\frac{1}{2\sqrt{3}} \\ -\frac{1}{\sqrt{6}}, \end{bmatrix}we are looking at the system

\begin{bmatrix} 2 & \frac{3}{2} & 1 \\ 0 & \frac{3}{\sqrt{12}} & \frac{2}{\sqrt{12}} \\ 0 & 0 & \frac{2}{\sqrt{6}} \end{bmatrix}x =\begin{bmatrix} \frac{3}{2} \\ -\frac{1}{2\sqrt{3}} \\ -\frac{1}{\sqrt{6}} \end{bmatrix}.Solving this system yields that

x_0 = \begin{bmatrix} 1 \\ 0 \\ -\frac{1}{2} \end{bmatrix}is a least-squares solution to

Ax = b.

Let us set this system up in python and use numpy.linalg.solve.

import numpy as np

# Define matrix and vector

A = np.array([[1,0,0],[1,1,0],[1,1,1],[1,1,1]])

b = np.array([[1],[1],[1],[0]])

# Take the QR decomposition of A

Q, R = np.linalg.qr(A)

# Solve the linear system Rx = Q.T b

beta = np.linalg.solve(R,Q.T @ b)

This yields

>>> beta

array([[ 1.00000000e+00],

[ 6.40987562e-17],

[-5.00000000e-01]])

which agrees with our exact least-squares solution.

Note that numpy.linalg.lstsq still gives a ever so slightly different result.

>>> np.linalg.lstsq(A,b)[0]

array([[ 1.00000000e+00],

[ 2.22044605e-16],

[-5.00000000e-01]])

Let's go back to the house example. While we're at it, let's get used to using pandas to make a dataframe.

import numpy as np

import pandas as pd

# First let us make a dictionary incorporating our data.

# Each entry corresponds to a column (feature of our data)

data = {

'Square ft': [1600, 2100, 1550, 1600, 2000],

'Bedrooms': [3, 4, 2, 3, 4],

'Price': [500, 650, 475, 490, 620]

}

# Create a pandas DataFrame

df = pd.DataFrame(data)

# Create our matrix X and our target y

X = df[["Square ft", "Bedrooms"]].to_numpy()

y = df[["Price"]].to_numpy()

# Augment X with a column of 1's (intercept)

X_aug = np.hstack((np.ones((X.shape[0], 1)), X))

# Perform QR decomposition

Q, R = np.linalg.qr(X_aug)

# Solve the upper triangular system Rx = Q^Ty

beta = np.linalg.solve(R, Q.T @ y)

Let's look at the output.

>>> Q

array([[-0.4472136 , 0.32838365, 0.40496317],

[-0.4472136 , -0.63745061, -0.22042299],

[-0.4472136 , 0.42496708, -0.7689174 ],

[-0.4472136 , 0.32838365, 0.40496317],

[-0.4472136 , -0.44428376, 0.17941406]])

>>> R

array([[-2.23606798e+00, -3.95784032e+03, -7.15541753e+00],

[ 0.00000000e+00, -5.17687164e+02, -1.50670145e+00],

[ 0.00000000e+00, 0.00000000e+00, 7.27908474e-01]])

>>> beta

array([-3.05053797e-13, 3.00000000e-01, 5.00000000e+00])

As we can see, the least-squares solution agrees with what we got by hand and by other python methods (if we agree that the tiny first component is essentially zero).

The QR decomposition of a matrix is also useful for computing orthogonal projections.

Theorem. Let

Abe anm \times nmatrix with full column rank. IfA = QRis a QR decomposition, thenQQ^Tis the projection onto the column space ofA, i.e.,QQ^Tb = \text{Proj}_{\text{Col}(A)}bfor allb \in \mathbb{R}^m.

Let's see what our range projections are for the matrices above. Note that the first example above will have the orthogonal projection just being

\begin{bmatrix} 1 \\ & 1 \\ & & 1\\ & & & 0 \end{bmatrix}.

Let's look at the other matrix.

Example. Working with the matrix

A = \begin{bmatrix} 1 & 0 & 0 \\ 1 & 1 & 0 \\ 1 & 1 & 1 \\ 1 & 1 & 1 \end{bmatrix},the projection onto the column space if given by

QQ^T = \begin{bmatrix} 1 \\ & 1 \\ & & \frac{1}{2} & \frac{1}{2} \\ & & \frac{1}{2} & \frac{1}{2} \end{bmatrix}.This is a well-understood projection: it is the direct sum of the identity on

\mathbb{R}^2and the projection onto the liney = xin\mathbb{R}^2.

Now let's use python to implement the projection.

import numpy as np

# Create our matrix A

A = np.array([[1,0,0],[1,1,0],[1,1,1],[1,1,1]])

# Take the QR decomposition

Q, R = np.linalg.qr(A)

# Create the range projection

P = Q @ Q.T

The output gives

array([[1.00000000e+00, 2.89687929e-17, 2.89687929e-17, 2.89687929e-17],

[2.89687929e-17, 1.00000000e+00, 7.07349921e-17, 7.07349921e-17],

[2.89687929e-17, 7.07349921e-17, 5.00000000e-01, 5.00000000e-01],

[2.89687929e-17, 7.07349921e-17, 5.00000000e-01, 5.00000000e-01]])

As we can see, the two off-diagonal blocks are all tiny, hence we treat them as zero. Note that if they were not actually zero, then this wouldn't actually be a projection. This can cause some problems. So let's fix this by introducing some tolerances.

Let's write a function to implement this, assuming that columns of A are linearly independent.

import numpy as np

def proj_onto_col_space(A):

# Take the QR decomposition

Q,R = np.linalg.qr(A)

# The projection is just Q @ Q.T

P = Q @ Q.T

return P

We'll come back to this later. We should really be incorporating some sort of error tolerance so that things are super super tiny can actually just be sent to zero.

Remark. Another way to get the projection onto the column space of an

n \times pmatrixAof full column rank is to takeP = A(A^TA)^{-1}A^T.Indeed, let

b \in \mathbb{R}^nand letx_0 \in \mathbb{R}^pbe a solution to the normal equationsA^TAx_0 = A^Tb.Then

x_0 = (A^TA)^{-1}A^Tband soAx_0 = A(A^TA^{-1})A^Tbis the (unique!) vector in the column space ofAwhich is closest tob, i.e., the projection ofbonto the column space ofA. However, taking transposes, multiplying, and inverting is not what we would like to do numerically.

Singular Value Decomposition

The SVD is a very important matrix decomposition in both data science and linear algebra.

Theorem. For any matrix

n \times pmatrixX, there exist an orthogonaln \times nmatrixU, an orthogonalp \times pmatrixV, and a diagonaln \times pmatrix\Sigmawith non-negative entries such thatX = U\Sigma V^T.

- The columns of

Uare left left singular vectors.- The columns of

Vare the right singular vectors.\Sigmahas singular values\sigma_1 \geq \sigma_2 \geq \cdots \geq \sigma_r > 0on its diagonal, whereris the rank ofX.

Remark. The SVD is clearly a generalization of matrix diagonalization, but it also generalizes the polar decomposition of a matrix. Recall that every

n \times nmatrixAcan be written asA = UPwhereUis orthogonal (or unitary) andPis a positive matrix. This is because ifA = U_0\Sigma V^Tis the SVD for

A, then\Sigmais ann \times ndiagonal matrix with non-negative entries, hence any orthogonal conjugate of it is positive, and soA = (U_0V^T)(V\Sigma V^T).Take

U = U_0V^TandP = V\Sigma V^T.

By hand, the algorithm for computing an SVD is as follows.

- Both

AA^TandA^TAare symmetric (they are positive in fact), and so they can be orthogonally diagonalized; one can form an orthogonal basis of eigenvectors. Letv_1,\dots,v_pbe an orthonormal basis of eigenvectors for\mathbb{R}^pwhich correspond to eigenvectors ofA^TAin decreasing order. Suppose thatA^TAhasrnon-zero eigenvalues. LetVbe the matrix whose columns contain the $v_i$'s. This gives our right singular vectors and our singular values. - Let

u_i = \frac{1}{\sigma_i}Av_ifori = 1,\dots,r, and extend this collection of vectors to an orthonormal basis for\mathbb{R}^nif necessary. LetUbe the corresponding matrix. - Let

\Sigmabe then \times pmatrix whose diagonal entries are\sigma_1 \geq \sigma_2 \geq \cdots \geq \sigma_r, and then zeroes if necessary.

Example. Let us compute the SVD of

A = \begin{bmatrix} 3 & 2 & 2 \\ 2 & 3 & -2 \end{bmatrix}.First we note that

A^TA = \begin{bmatrix} 13 & 12 & 2 \\ 12 & 13 & -2 \\ 2 & -2 & 8 \end{bmatrix},which has eigenvalues

25,9,0with corresponding eigenvectors\begin{bmatrix} 1 \\ 1 \\ 0 \end{bmatrix}, \begin{bmatrix} 1 \\ -1 \\ 4 \end{bmatrix}, \begin{bmatrix} -2 \\ 2 \\ 1 \end{bmatrix}.Normalizing, we get

V = \begin{bmatrix} \frac{1}{\sqrt{2}} & \frac{1}{3\sqrt{2}} & -\frac{2}{3} \\ \frac{1}{\sqrt{2}} & -\frac{1}{3\sqrt{2}} & \frac{2}{3} \\ 0 & \frac{4}{3\sqrt{2}} & \frac{1}{3} \end{bmatrix}.Now we set

u_1 = \frac{1}{5}Av_1andu_2 = \frac{1}{3}Av_2to getU = \begin{bmatrix} \frac{1}{\sqrt{2}} & \frac{1}{\sqrt{2}} \\ \frac{1}{\sqrt{2}} & -\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}} \end{bmatrix}.So

A = \begin{bmatrix} \frac{1}{\sqrt{2}} & \frac{1}{\sqrt{2}} \\ \frac{1}{\sqrt{2}} & -\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}} \end{bmatrix} \begin{bmatrix} 5 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 3 & 0 \end{bmatrix} \begin{bmatrix} \frac{1}{\sqrt{2}} & \frac{1}{3\sqrt{2}} & -\frac{2}{3} \\ \frac{1}{\sqrt{2}} & -\frac{1}{3\sqrt{2}} & \frac{2}{3} \\ 0 & \frac{4}{3\sqrt{2}} & \frac{1}{3} \end{bmatrix}^Tis our SVD decomposition.

We note that in practice, we avoid the computation of X^TX because if the entries of X have errors, then these errors will be squared in X^TX. There are better computational tools to get singular values and singular vectors which are more accurate. This is what our python tools will use.

Let's use numpy.linalg.svd for the above matrix.

import numpy as np

#Define our matrix

A = np.array([[3,2,2],[2,3,-2]])

# Take the SVD

U, S, Vh = np.linalg.svd(A)

Our SVD matrices are

>>> U

array([[-0.70710678, -0.70710678],

[-0.70710678, 0.70710678]])

>>> S

array([5., 3.])

# Note that Vh already gives the transpose of the matrix V we get

# in our SVD. So we'll take the transpose again to get

# the appropriate rows

>>> Vh.T

array([[-7.07106781e-01, -2.35702260e-01, -6.66666667e-01],

[-7.07106781e-01, 2.35702260e-01, 6.66666667e-01],

[-6.47932334e-17, -9.42809042e-01, 3.33333333e-01]])

Because the eigenvalues of the hermitian squares of

\begin{bmatrix} 1 & 1 & 1\\ 0 & 1 & 1 \\ 0 & 0 & 1 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 \end{bmatrix} \text{ and } \begin{bmatrix} 1 & 0 & 0 \\ 1 & 1 & 0 \\ 1 & 1 & 1 \\ 1 & 1 & 1 \end{bmatrix}

are quite atrocious, an exact SVD decomposition is difficult to compute by hand. However, we can of course use python.

import numpy as np

# Define our matrices

A = np.array([[1,1,1],[0,1,1],[0,0,1],[0,0,0]])

B = np.array([[1,0,0],[1,1,0],[1,1,1],[1,1,1]])

# SVD decomposition

U_A, S_A, Vh_A = np.linalg.svd(A)

U_B, S_B, Vh_B = np.linalg.svd(B)

The resulting matrices are

>>> U_A

array([[ 0.73697623, 0.59100905, 0.32798528, 0. ],

[ 0.59100905, -0.32798528, -0.73697623, 0. ],

[ 0.32798528, -0.73697623, 0.59100905, 0. ],

[ 0. , 0. , 0. , 1. ]])

>>> S_A

array([2.2469796 , 0.80193774, 0.55495813])

>>> Vh_A.T

array([[ 0.32798528, 0.73697623, 0.59100905],

[ 0.59100905, 0.32798528, -0.73697623],

[ 0.73697623, -0.59100905, 0.32798528]])

>>> U_B

array([[-2.41816250e-01, 7.12015746e-01, -6.59210496e-01,

0.00000000e+00],

[-4.52990541e-01, 5.17957311e-01, 7.25616837e-01,

6.71536163e-17],

[-6.06763739e-01, -3.35226641e-01, -1.39502200e-01,

-7.07106781e-01],

[-6.06763739e-01, -3.35226641e-01, -1.39502200e-01,

7.07106781e-01]])

>>> S_B

array([2.8092118 , 0.88646771, 0.56789441])

>>> Vh_B.T

array([[-0.67931306, 0.63117897, -0.37436195],

[-0.59323331, -0.17202654, 0.7864357 ],

[-0.43198148, -0.75632002, -0.49129626]])

Another final note is that the operator norm of a matrix A agrees with its largest singular value.

Pseudoinverses and using the SVD

The SVD can be used to determine a least-squares solution for a given system. Recall that if v_1,\dots,v_p is an orthonormal basis for \mathbb{R}^p consisting of eigenvectors of A^TA, arranged so that they correspond to eigenvalues \sigma_1 \geq \sigma_2 \geq \cdots \geq \sigma_r, then \{Av_1,\dots,Av_r\} is an orthogonal basis for the column space of A. In essence, this means that when we have our left singular vectors u_1,\dots,u_n (constructed based on our algorithm as above), we have that the first r vectors form an orthonormal basis for the column space of A, and that the remaining n - r vectors form an orthonormal basis for the perp of the column space of A (which is also equal to the nullspace of A^T).

Definition. Let

Abe ann \times pmatrix and suppose that the rank ofAisr \leq \min\{n,p\}. Suppose thatA = U\Sigma V^Tis the SVD, where the singular values are decreasing. PartitionU = \begin{bmatrix} U_r & U_{n-r} \end{bmatrix} \text{ and } V = \begin{bmatrix} V_r & V_{p-r} \end{bmatrix}into submatrices, where

U_randV_rare the matrices whose columns are the firstrcolumns ofUandVrespectively. SoU_risn \times randV_risp \times r. LetDbe the diagonalr \times rmatrices whose diagonal entries are\sigma_1,\dots, \sigma_r, so that\Sigma = \begin{bmatrix} D & 0 \\ 0 & 0 \end{bmatrix}and note that

A = U_rDV_r^T.We call this the reduced singular value decomposition of

A. Note thatDis invertible, and its inverse is simplyD = \begin{bmatrix} \sigma_1^{-1} \\ & \sigma_2^{-1} \\ & & \ddots \\ & & & \sigma_r^{-1} \end{bmatrix}.The pseudoinverse (or Moore-Penrose inverse) of

Ais the matrixA^+ = V_rD^{-1}U_r^T.

We note that the pseudoinverse A^+ is a p \times n matrix.

With the pseudoinverse, we can actually find least-squares solutions quite easily. Indeed, if we are looking for the least-squares solution to the system Ax = b, define

x_0 = A^+b.

Then

\begin{split} Ax_0 &= (U_rDV_r^T)(V_rD^{-1}U_r^Tb) \\ &= U_rDD^{-1}U_r^Tb \\ &= U_rU_r^Tb \end{split}

As mentioned before, the columns of U_r form an orthonormal basis for the column space of A and so U_rU_r^T is the orthogonal projection onto the range of A. That is, Ax_0 is precisely the projection of b onto the column space of A, meaning that this yields a least-squares solution. This gives the following.

Theorem. Let

Abe ann \times pmatrix andb \in \mathbb{R}^n. Thenx_0 = A^+bis a least-squares solution to

Ax = b.

Taking pseudoinverses is quite involved. We'll do one example by hand, and then use python -- and we'll see something go wrong! There is a function numpy.linalg.pinv in numpy that will take a pseudoinverse. We can also just use numpy.linalg.svd and do the process above.

Example. We have the following SVD

A = U\Sigma V^T.\begin{bmatrix} 1 & 1 & 2\\ 0 & 1 & 1 \\ 1 & 0 & 1 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 \end{bmatrix} = \begin{bmatrix} \sqrt{\frac{2}{3}} & 0 & 0 & -\frac{1}{\sqrt{3}} \\ \frac{1}{\sqrt{6}} & \frac{1}{\sqrt{2}} & 0 & \frac{1}{\sqrt{3}} \\ \frac{1}{\sqrt{6}} & -\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}} & 0 & \frac{1}{\sqrt{3}} \\ 0 & 0 & 1 & 0 \end{bmatrix} \begin{bmatrix} 3 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 1 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 \end{bmatrix}\begin{bmatrix} \frac{1}{\sqrt{6}} & -\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}} & -\frac{1}{\sqrt{3}} \\ \frac{1}{\sqrt{6}} & \frac{1}{\sqrt{2}} & -\frac{1}{\sqrt{3}} \\ \sqrt{\frac{2}{3}} & 0 & \frac{1}{\sqrt{3}} \end{bmatrix}^T.Can we find a least-squares solution to

Ax = b, whereb = \begin{bmatrix} 1 \\ 1 \\ 1 \\ 1 \end{bmatrix}?The pseudoinverse of

Ais\begin{split} A^+ &= \begin{bmatrix} \frac{1}{\sqrt{6}} & -\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}} \\ \frac{1}{\sqrt{6}} & \frac{1}{\sqrt{2}} \\ \sqrt{\frac{2}{3}} & 0 \end{bmatrix} \begin{bmatrix} 3 \\ & 1 \end{bmatrix} \begin{bmatrix} \sqrt{\frac{2}{3}} & 0 \\ \frac{1}{\sqrt{6}} & \frac{1}{\sqrt{2}} \\ \frac{1}{\sqrt{6}} & -\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}} \\ 0 & 0 \end{bmatrix}^T \\ &= \begin{bmatrix} \frac{1}{9} & -\frac{4}{9} & \frac{5}{9} & 0 \\ \frac{1}{9} & \frac{5}{9} & -\frac{4}{9} & 0 \\ \frac{2}{9} & \frac{1}{9} & \frac{1}{9} & 0\end{bmatrix}, \end{split}and so a least-squares solution is given by

\begin{split} x_0 &= A^+b \\ &= \begin{bmatrix} \frac{1}{9} & -\frac{4}{9} & \frac{5}{9} & 0 \\ \frac{1}{9} & \frac{5}{9} & -\frac{4}{9} & 0 \\ \frac{2}{9} & \frac{1}{9} & \frac{1}{9} & 0\end{bmatrix}\begin{bmatrix} 1 \\ 1 \\ 1 \\ 1 \end{bmatrix} \\ &= \begin{bmatrix} \frac{2}{9} \\ \frac{2}{9} \\ \frac{4}{9} \end{bmatrix}. \end{split}

Now let's do this with python, and see an example of how things can go wrong. We'll try to take the pseudoinverse manually first.

import numpy as np

# Create our matrix A and our target b

A = np.array([[1,1,2],[0,1,1],[1,0,1],[0,0,0]])

b = np.array([[1],[1],[1],[1]])

# Take the SVD decomposition

U, S, Vh = np.linalg.svd(A)

# Prepare the pseudoinverse

# Recall that we invert the non-zero diagonal entries of the diagonal matrix.

# So we first build S_inv to be the appropriate size

S_inv = np.zeros((Vh.shape[0], U.shape[0]))

# We then fill in the appropriate values on the diagonal

S_inv[:len(S), :len(S)] = np.diag(1/S)

# Build the pseudoinverse

A_pinv = Vh.T @ S_inv @ U.T

# Compute the least-squares solution

beta = A_pinv @ b

What is the result?

>>> beta

array([[ 2.74080345e+15],

[ 2.74080345e+15],

[-2.74080345e+15]])

This is WAY off the mark. So what happened? Well, when we look at our singular values, we have

>>> S

array([3.00000000e+00, 1.00000000e+00, 1.21618839e-16])

As we got this matrix numerically, the last entry is actually non-zero, but tiny. This isn't exactly what's going on since we know that the rank of A is 2. So when we invert the singular values and throw them on the diagonal, have 1/1.21618839e-16 which is a very large value. This value then messes up the rest of the computation. So how do we fix this? One can set tolerances in numpy, but we'll get to that later. Let's just note that numpy.linalg.pinv will already incorporate this. Let's see what we get.

import numpy as np

# Create our matrix A and our target b

A = np.array([[1,1,2],[0,1,1],[1,0,1],[0,0,0]])

b = np.array([[1],[1],[1],[1]])

# Build the pseudoinverse

A_pinv = np.linalg.pinv(A)

# Compute the least-squares solution

beta = A_pinv @ b

>>> A_pinv

array([[ 0.11111111, -0.44444444, 0.55555556, 0. ],

[ 0.11111111, 0.55555556, -0.44444444, 0. ],

[ 0.22222222, 0.11111111, 0.11111111, 0. ]])

>>> beta

array([[0.22222222],

[0.22222222],

[0.44444444]])

The Condition Number

Numerical calculations involving matrix equations are quite reliable if we use the SVD. This is because the orthogonal matrices U and V preserve lengths and angles, leaving the stability of the problem to be governed by the singular values of the matrix X. Recall that if X = U\Sigma V^T, then solving the least-squares problem involves dividing by the non-zero singular values \sigma_i of X. If these values are very small, their inverses become very large, and this will amplify any numerical errors.

Definition. Let

Xbe ann \times pmatrix and let\sigma_1 \geq \cdots \geq \sigma_rbe the non-zero singular values ofX. The condition number ofXis the quotient\kappa(X) = \frac{\sigma_1}{\sigma_r}of the largest and smallest non-zero singular values.

A condition number close to 1 indicates a well-conditioned problem, while a large condition number indicates that small perturbations in data may lead to large changes in computation. Geometrically, \kappa(X) measures how much X distorts space.

Example. Consider the matrices

A = \begin{bmatrix} 1 \\ & 1 \end{bmatrix} \text{ and } B = \begin{bmatrix} 1 \\ & \frac{1}{10^6} \end{bmatrix}.The condition numbers are

\kappa(A) = 1 \text{ and } \kappa(B) = 10^6.Inverting

X_2includes dividing by\frac{1}{10^6}, which will amplify errors by10^6.

Let's look our main example in python by using numpy.linalg.cond.

import numpy as np

import pandas as pd

# First let us make a dictionary incorporating our data.

# Each entry corresponds to a column (feature of our data)

data = {

'Square ft': [1600, 2100, 1550, 1600, 2000],

'Bedrooms': [3, 4, 2, 3, 4],

'Price': [500, 650, 475, 490, 620]

}

# Create a pandas DataFrame

df = pd.DataFrame(data)

# Create out matrix X

X = df[['Square ft', 'Bedrooms']].to_numpy()

# Check the condition number

cond_X = np.linalg.cond(X)

Let's see what we got.

>>> cond_X

np.float64(4329.082589067693)

so this is quite a high condition number! This should be unsurprising, as clearly the number of bedrooms is correlated to the size of a house (especially so in our small toy example).

A note on other norms

There are other canonical choices of norms for vectors and matrices. While L^2 leads naturally to least-squares problems with closed-form solutions, other norms induce different geometries and different optimal solutions. From the linear algebra perspective, changing the norm affects:

- the shape of the unit ball,

- the geometry of approximation,

- the numerical behaviour of optimization problems.

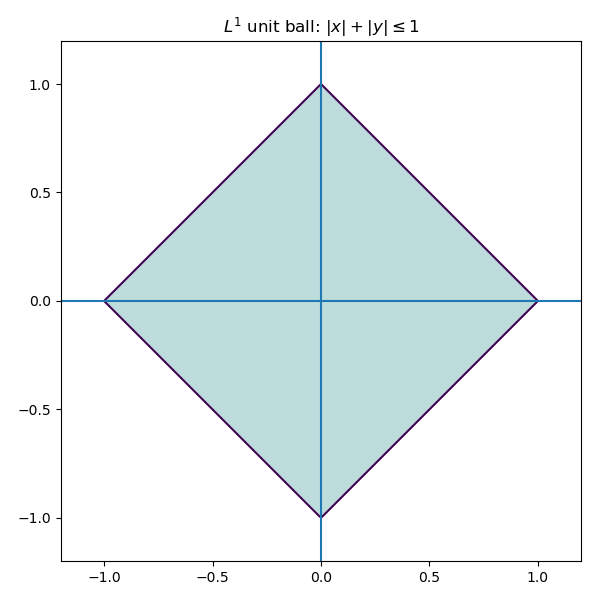

L^1 norm (Manhattan distance)

The L^1 norm of a vector x = (x_1,\dots,x_p) \in \mathbb{R}^p is defined as

\|x\|_1 = \sum |x_i|.

Minimizing the L^1 norm is less sensitive to outliers. Geometrically, the L^1 unit ball in \mathbb{R}^2 is a diamond (a rotated square), rather than a circle.

Consequently, optimization problems involving L^1 tend to produce solutions which live on the corners of this polytope.

Solutions often require linear programming or iterative reweighted least squares.

L^1 based methods (such as LASSO) tend to set coefficients to be exactly zero. Unlike with L^2, the minimization problem for L^1 does not admit a closed form solution. Algorithms include:

- linear programming formulations,

- iterative reweighted least squares,

- coordinate descent methods.

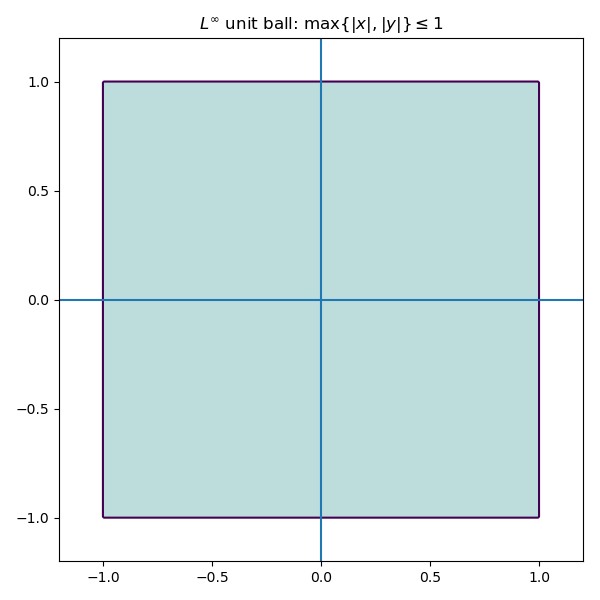

L^{\infty} norm (max/supremum norm)

The supremum norm defined as

\|x\|_{\infty} = \max |x_i|

seeks to control the worst-case error rather than the average error. Minimizing this norm is related to Chebyshev approximation by polynomials.

Geometrically, the unit ball of \mathbb{R}^2 with respect to the L^{\infty} norm looks like a square.

Problems involving the L^{\infty} norm are often formulated as linear programs, and are useful when worst-case guarantees are more important than optimizing average performance.

Matrix norms

There are also various norms on matrices, each highlighting a different aspect of the associated linear transformation.

-

Frobenius norm. This is an important norm, essentially the analogue of the

L^2norm for matrices. It is the Euclidean norm if you think of your matrix as a vector, forgetting its rectangular shape. ForA = (a_{ij})a matrix, the Frobenius norm\|A\|_F = \sqrt{\sum a_{ij}^2}is the square root of the sum of squares of all the entries. This treats a matrix as a long vector and is invariant under orthogonal transformations. As we'll see, it plays a central role in:

- least-squares problems,

- low-rank approximation,

- principal component analysis.

In particular, the truncated SVD yields a best low-rank approximation of a matrix with respect to the Frobenius norm.

We also that that the Frobenius norm can be written in terms of tracial data. We have that

\|A\|_F^2 = \text{Tr}(A^TA) = \text{Tr}(AA^T). -

Operator norm (spectral norm). This is just the norm as an operator

A: \mathbb{R}^p \to \mathbb{R}^n, where\mathbb{R}^pand\mathbb{R}^nare thought of as Hilbert spaces:\|A\| = \max_{\|x\|_2 = 1}\|Ax\|_2.This norm measures how big of an amplification

Acan apply, and is equal to the largest singular value ofA. This norm is related to stability properties, and is the analogue of theL^{\infty}norm. -

Nuclear norm. The nuclear norm, defined as

\|A\|_* = \sum \sigma_i,is the sum of the singular values. When

Ais square, this is precisely the trace-class norm, and is the analogue of theL^1norm. This norm acts as a generalization of the concept of rank.

A note on regularization

Regularization introduces additional constraints or penalties to stabilize ill-posed problems. From the linear algebra point of view, regularization modifies the singular value structure of a problem.

- Ridge regression: add a positive multiple

\lambda\cdot Iof the identity toX^TXwhich will artificially inflate small singular values. - This dampens unstable directions while leaving well-conditioned directions largely unaffected.

Geometrically, regularization reshapes the solution space to suppress directions that are poorly supported by the data.

A note on solving multiple targets concurrently

Suppose now that we were interested in solving several problems concurrently; that is, given some data points, we would like to make k predictions. Say we have our n \times p data matrix X, and we want to make k predictions y_1,\dots,y_k. We can then set the problem up as finding a best solution to the matrix equation

XB = Y

where B will be a p \times k matrix of parameters and Y will be the p \times k matrix whose columns are y_1,\dots,y_k.

Polynomial Regression

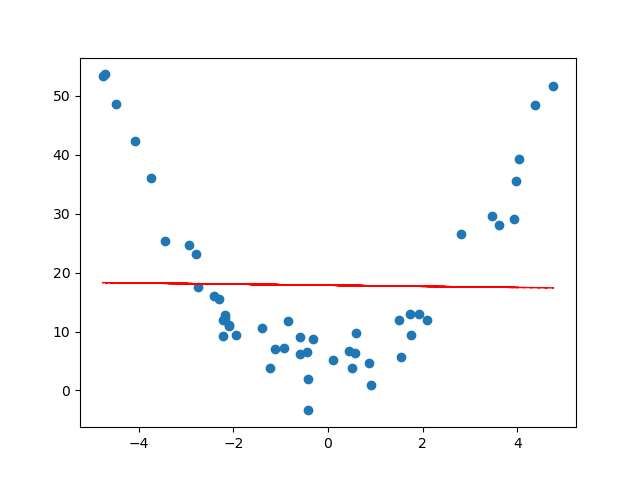

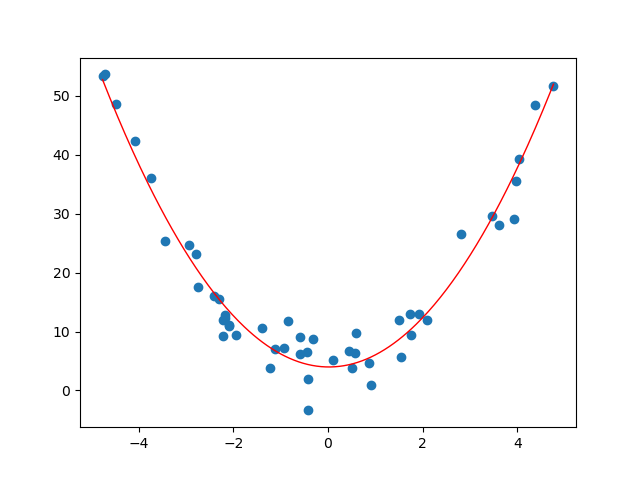

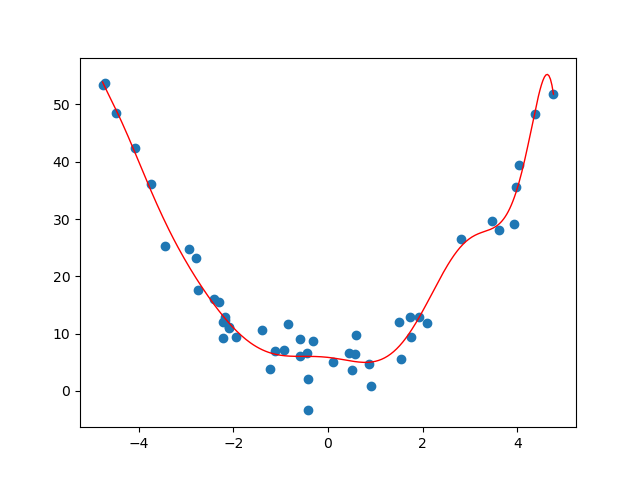

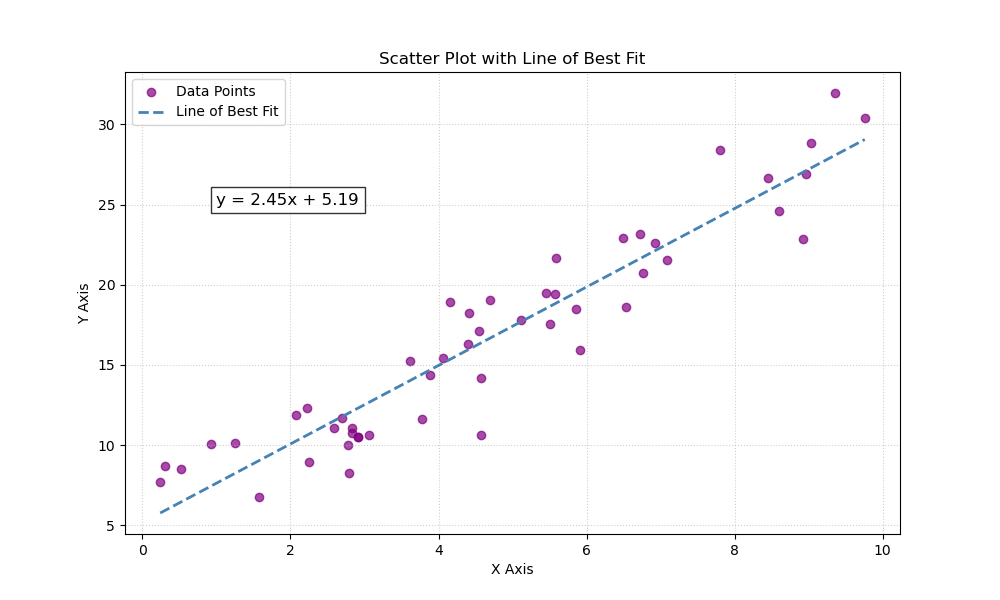

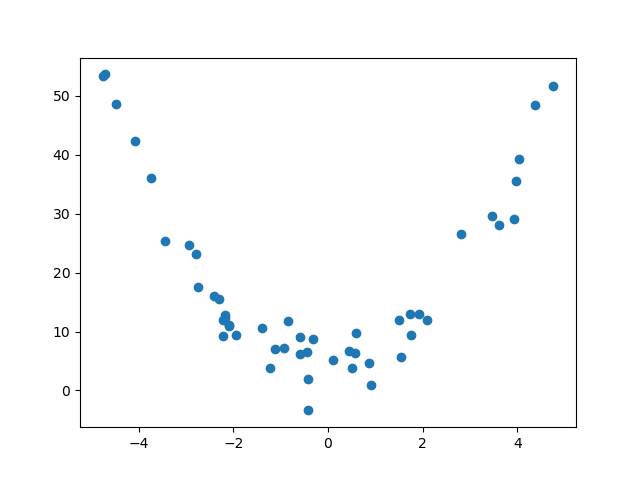

Sometimes fitting a line to a set of n data points clearly isn't the right thing to do. To emphasize the limitations of linear models, we generate data from a purely quadratic relationship. In this setting, the space of linear functions is not rich enough to capture the underlying structure, and the linear least-squares solution exhibits systematic error. Expanding the feature space to include quadratic terms resolves this issue.

For example, suppose our data looked like the following.

If we try to find a line of best fit, we get something that doesn't really describe or approximate our data at all...

This is an example of underfitting data, and we can do better. The same linear regression ideas work for fitting a degree d polynomial model to a set of n data points. Before, when trying to fit a line to points (x_1,y_1),\dots,(x_n,y_n), we had the following matrices

\tilde{X} = \begin{bmatrix} 1 & x_1 \\ \vdots & \vdots \\ 1 & x_n \end{bmatrix}, y = \begin{bmatrix} y_1 \\ \vdots \\ y_n \end{bmatrix}, \tilde{\beta} = \begin{bmatrix} \beta_0 \\ \beta_1 \end{bmatrix}

in the matrix equation

\tilde{X}\tilde{\beta} = y,

and we were trying to find a vector \tilde{\beta} which gave a best possible solution. This would give us a line y = \beta_0 + \beta_1x which best approximates the data. To fit a polynomial y = \beta_0 + \beta_1x + \beta_2x^2 + \cdots + \beta_d^dx^d to the data, we have a similar set up.

Definition. The Vandermonde matrix is the

n \times (d+1)matrixV = \begin{bmatrix} 1 & x_1 & x_1^2 & \cdots & x_1^d \\ 1 & x_2 & x_2^2 & \cdots & x_2^d \\ \vdots & \vdots & \ddots & \vdots \\ 1 & x_n & x_n^2 & \cdots & x_n^d \end{bmatrix}.

With the Vandermonde matrix, to find a polynomial function of best fit, one just needs to find a least-squares solution to the matrix equation

V\tilde{\beta} = y.

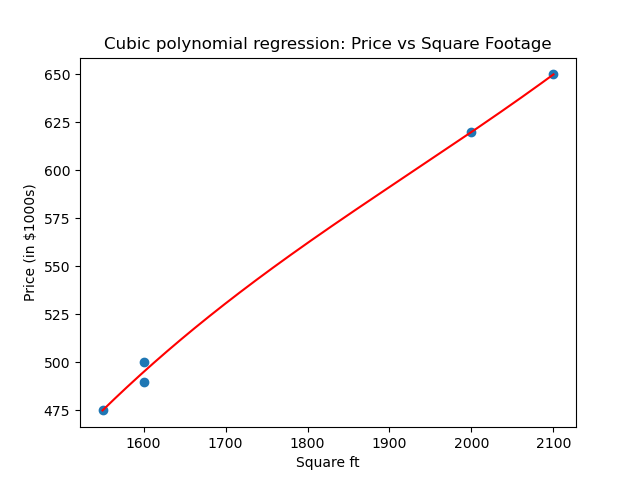

With the generated data above, we get the following curve.

Solving these problems can be done with python. One can use numpy.polyfit and numpy.poly1d.

Example. Consider the following data.

House Square ft Bedrooms Price (in $1000s) 0 1600 3 500 1 2100 4 650 2 1550 2 475 3 1600 3 490 4 2000 4 620 Suppose we wanted to predict the price of a house based on the square footage and we thought the relationship was cubic (it clearly isn't, but hey, for the sake of argument). So really we are looking at the subset of data

House Square ft Price (in $1000s) 0 1600 500 1 2100 650 2 1550 475 3 1600 490 4 2000 620 Our Vandermonde matrix will be

V = \begin{bmatrix} 1 & 1600 & 1600^2 & 1600^3 \\ 1 & 2100 & 2100^2 & 2100^3 \\ 1 & 1550 & 1550^2 & 1550^3 \\ 1 & 1600 & 1600^2 & 1600^3 \\ 1 & 2000 & 2000^2 & 2000^3 \end{bmatrix}and our target vector will be

y = \begin{bmatrix} 500 \\ 650 \\ 475 \\ 490 \\ 620 \end{bmatrix}.As we can see, the entries of the Vandermonde matrix get very very large very fast. One can, if they are so inclined, compute a least-squares solution to

V\tilde{\beta} = yby hand. Let's not, but let us find, using python, a "best" cubic approximation of the relationship between the square footage and price.

We will use numpy.polyfit, numpy.pold1d and numpy.linspace.

import numpy as np

import pandas as pd

import matplotlib as plt

# First let us make a dictionary incorporating our data.

# Each entry corresponds to a column (feature of our data)

data = {

'Square ft': [1600, 2100, 1550, 1600, 2000],

'Bedrooms': [3, 4, 2, 3, 4],

'Price': [500, 650, 475, 490, 620]

}

# Create a pandas DataFrame

df = pd.DataFrame(data)

# Extract x (square footage) and y (price)

x = df["Square ft"].to_numpy(dtype=float)

y = df["Price"].to_numpy(dtype=float)

# Degree of polynomial

degree = 3 # cubic

# Polyfit directly on x

cubic = np.poly1d(np.polyfit(x,y, degree))

# Add fitted polynomial line and scatter plot

polyline = np.linspace(x.min(),x.max())

plt.scatter(x,y, label="Observed data")

plt.plot(polyline, cubic(polyline), 'r', label="Cubic best fit")

plt.xlabel("Square ft")

plt.ylabel("Price (in $1000s)")

plt.title("Cubic polynomial regression: Price vs Square Footage")

plt.show()

So we get a cubic of best fit.

Here numpy.polyfit computes the least-squares solution in the polynomial basis 1, x, x^2, x^3, i.e., it solves the Vandermonde least-squares problem. So what is our cubic polynomial?

>>> cubic

poly1d([ 3.08080808e-07, -1.78106061e-03, 3.71744949e+00, -2.15530303e+03])

The first term is the degree 3 term, the second the degree 2 term, the third the degree 1 term, and the fourth is the constant term.

What can go wrong?

We are often dealing with imperfect data, so there is plenty that could go wrong. Here are some basic cases of where things can break down.

- Perfect multicolinearity: non-invertible

\tilde{X}^T\tilde{X}. This happens when one feature is a perfect combination of the others. This means that the columns of the matrix\tilde{X}are linearly dependent, and so infinitely many solutions will exist to the least-squares problem.- For example, if you are looking at characteristics of people and you have height in both inches and centimeters.

- Almost multicolinearity: this happens when one features is almost a perfect combination of the others. From the linear algebra perspective, the columns of

\tilde{X}might not be dependent, but they will be be almost linearly dependent. This will cause problems in calculation, as the condition number will become large and amplify numerical errors. The inverse will blow up small spectral components. - More features than observations: this means that our matrix

\tilde{X}will be wider than it is high. Necessarily, this means that the columns are linearly dependent. Regularization or dimensionality reduction becomes essential. - Redundant or constant features: this is when there is a characteristic that is satisfied by each observation. In terms of the linear algebraic data, this means that one of the columns of

Xis constant.- e.g., if you are looking at characteristics of penguins, and you have "# of legs". This will always be two, and doesn't add anything to the analysis.

- Underfitting: the model lacks sufficient expressivity to capture the underlying structure. For example, see the section on polynomial regression -- sometimes one might want a curve vs. a straight line.

- Overfitting: the model captures noise rather than structure. Often due to model complexity relative to data size. Polynomial regression can give a nice visualization of overfitting. For example, if we worked with the same generated quadratic data from the polynomial regression section, and we tried to approximation it by a degree 11 polynomial, we get the following.

- Outliers: large deviations can dominate the

L^2norm. This is where normalization might be key. - Heteroscedasticity: this is when the variance of noise changes across observations. Certain least-squares assumptions will break down.

- Condition number: a large condition number indicates numerical instability and sensitivity to perturbation, even when formal solutions exist.

- Insufficient tolerance: in numerical algorithms, thresholds used to determine rank or invertibility must be chosen carefully. Poor choices can lead to misleading results.

The point is that many failures in data science are not conceptual, but they happen geometrically and numerically. Poor choices lead to poor results.

Principal Component Analysis

Principal Component Analysis (PCA) addresses the issues of multicollinearity and dimensionality mentioned at the end of the previous section by transforming the data into a new coordinate system. The new axes -- called principal components -- are chosen to capture the maximum variance in the data. In linear algebra terms, we are finding a subspace of potentially smaller dimension that best approximates our data.

Example: Let us return to our house example. Suppose we decide to list the square footage in both square feet and square meters. Let's add this feature to our dataset.

House Square ft Square m Bedrooms Price (in $1000s) 0 1600 148 3 500 1 2100 195 4 650 2 1550 144 2 475 3 1600 148 3 490 4 2000 185 4 620 In this case, our associated matrix is:

X = \begin{bmatrix} 1600 & 148 & 3 & 500 \\ 2100 & 195 & 4 & 650 \\ 1550 & 144 & 2 & 475 \\ 1600 & 148 & 3 & 490 \\ 2000 & 185 & 4 & 620 \end{bmatrix}

There are a few problems with the above data and the associated matrix X (this time, we're not looking to make predictions, so we don't omit the last column).

- Redundancy: Square feet and square meters give the same information. It's just a matter of if you're from a civilized country or from an uncivilized country.

- Numerical instability: The columns of

Xare nearly linearly dependent. Indeed, the second column is almost a multiple of the first. Moreover, one can make a safe bet that the number of bedrooms increases as the square footage does, so that the first and third columns are correlated. - Interpretation difficulty: We used the square footage and bedrooms together in the previous section to predict the price of a house. However, because of their correlation, this obfuscates the true relationship, say, between the square footage and the price of a house, or the number of bedrooms and the price of a house.

So the question becomes: what do we do about this? We will try to get a smaller matrix (less columns) that contains the same, or a close enough, amount of information. The point is that the data is effectively lower-dimensional.

Let's do a little analysis on our dataset before progressing. Let's use pandas.DataFrame.describe, pandas.DataFrame.corr and numpy.linalg.cond. First, let's set up our data.

import numpy as np

import pandas as pd

# First let us make a dictionary incorporating our data.

# Each entry corresponds to a column (feature of our data)

data = {

'Square ft': [1600, 2100, 1550, 1600, 2000],

'Square m': [148, 195, 144, 148, 185],

'Bedrooms': [3, 4, 2, 3, 4],

'Price': [500, 650, 475, 490, 620]

}

# Create a pandas DataFrame

df = pd.DataFrame(data)

# Create out matrix X

X = df.to_numpy()

Now let's see what it has to offer.

# Describe the data

>>> df.describe()

Square ft Square m Bedrooms Price

count 5.000000 5.000000 5.00000 5.000000

mean 1770.000000 164.000000 3.20000 547.000000

std 258.843582 24.052027 0.83666 81.516869

min 1550.000000 144.000000 2.00000 475.000000

25% 1600.000000 148.000000 3.00000 490.000000

50% 1600.000000 148.000000 3.00000 500.000000

75% 2000.000000 185.000000 4.00000 620.000000

max 2100.000000 195.000000 4.00000 650.000000

# View correlations

>>> df.corr()

Square ft Square m Bedrooms Price

Square ft 1.000000 0.999886 0.900426 0.998810

Square m 0.999886 1.000000 0.894482 0.998395

Bedrooms 0.900426 0.894482 1.000000 0.909066

Price 0.998810 0.998395 0.909066 1.000000

# Check the condition number

>>> np.linalg.cond(X)

np.float64(8222.19067218415)

As we can see, everything is basically correlated, and we clearly have some redundancies.

This section is structured as follows.

Low-rank approximation via SVD

Let A be an n \times p matrix and let A = U\Sigma V^T be a SVD. Let u_1,\dots,u_n be the columns of U, v_1,\dots,v_p be the column of V, and \sigma_1 \geq \cdots \sigma_r > 0 be the singular values, where r \leq \min\{n,p\} is the rank of A. Then we have the reduced singular value decomposition (see Pseudoinverses and using the svd)

A = \sum_{i=1}^r \sigma_i u_iv_i^T

(note that u_i is a n \times 1 matrix and v_i is a p \times 1 matrix, so u_iv_i^T is some n \times p matrix).

The key idea is that if the rank of A is higher, say s, but the latter singular values are small, then we should still have an approximation like this. Say \sigma_{r+1},\dots,\sigma_{s} are tiny. Then

\begin{split} A &= \sum_{i=1}^s \sigma_i u_i v_i^T \\ &= \sum_{i=1}^r \sigma_i u_iv_i^T + \sum_{i=r+1}^{s} \sigma_i u_iv_i^T \\ &\approx \sum_{i=1}^r \sigma_iu_i v_i^T \end{split}.

So defining A_r := \sum_{i=1}^r \sigma_i u_iv_i^T, we are approximating A by A_r.

In what sense is this a good approximation though? Recall that the Frobenius norm of a matrix A is defined as the sqrt root of the sum of the squares of all the entries:

\|A\|_F = \sqrt{\sum_{i,j} a_{ij}^2}.

The Frobenius norm acts as a very nice generalization of the L^2 norm for vectors, and is an indispensable tool in both linear algebra and data science. The point is that this "approximation" above actually works in the Frobenius norm, and this reduced singular value decomposition in fact minimizes the error.

Theorem (Eckart–Young–Mirsky). Let

Abe ann \times pmatrix of rankr. Fork \leq r,\min_{B \text{ such that rank}(B) \leq k} \|A - B\|_F = \|A - A_k\|_F.The (at most) rank

kmatrixA_kalso realizes the minimum when optimizing for the operator norm.

Example. Recall that we have the following SVD:

\begin{bmatrix} 3 & 2 & 2 \\ 2 & 3 & -2 \end{bmatrix} = \begin{bmatrix} \frac{1}{\sqrt{2}} & \frac{1}{\sqrt{2}} \\ \frac{1}{\sqrt{2}} & -\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}} \end{bmatrix} \begin{bmatrix} 5 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 3 & 0 \end{bmatrix} \begin{bmatrix} \frac{1}{\sqrt{2}} & \frac{1}{3\sqrt{2}} & -\frac{2}{3} \\ \frac{1}{\sqrt{2}} & -\frac{1}{3\sqrt{2}} & \frac{2}{3} \\ 0 & \frac{4}{3\sqrt{2}} & \frac{1}{3} \end{bmatrix}^T.So if we want a rank-one approximation for the matrix, we'll do the reduced SVD. We have

\begin{split} A_1 &= \sigma_1u_1v_1^T \\ &= 5\begin{bmatrix} \frac{1}{\sqrt{2}} \\ \frac{1}{\sqrt{2}} \end{bmatrix}\begin{bmatrix} \frac{1}{\sqrt{2}} & \frac{1}{\sqrt{2}} & 0 \end{bmatrix} \\ &= \begin{bmatrix} \frac{5}{2} & \frac{5}{2} & 0 \\ \frac{5}{2} & \frac{5}{2} & 0 \end{bmatrix} \end{split}Now let's compute the (square of the) Frobenius norm of the difference

A - A_1. We have\begin{split} \|A - A_1\|_F^2 &= \left\| \begin{bmatrix} \frac{1}{2} & -\frac{1}{2} & 2 \\ -\frac{1}{2} & \frac{1}{2} & -2 \end{bmatrix}\right\|_F^2 \\ &= 4(\frac{1}{2})^2 + 2(2^2) = 9. \end{split}So the Frobenius distance between

AandA_1is 3, and we know by Eckart-Young-Mirsky that this is the smallest we can get when looking at the difference betweenAand a (at most) rank one2 \times 3matrix. As mentioned, the operator norm\|A - A_1\|also minimizes the distance (in operator norm). We know this to be the largest singular value. AsA - A_1has SVD\begin{bmatrix} \frac{1}{2} & -\frac{1}{2} & 2 \\ -\frac{1}{2} & \frac{1}{2} & -2 \end{bmatrix} = \begin{bmatrix} -\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}} & \frac{1}{\sqrt{2}} \\ \frac{1}{\sqrt{2}} & \frac{1}{\sqrt{2}} \end{bmatrix}\begin{bmatrix} 3 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 \end{bmatrix} \begin{bmatrix} -\frac{1}{3\sqrt{2}} & -\frac{4}{\sqrt{17}} & \frac{1}{3\sqrt{34}} \\ \frac{1}{3\sqrt{2}} & 0 & \frac{1}{3}\sqrt{\frac{17}{2}} \\ -\frac{2\sqrt{2}}{3} & \frac{1}{\sqrt{17}} & \frac{2}{3}\sqrt{\frac{2}{17}} \end{bmatrix},the operator norm is also 3.

Now let's do this in python. We'll set up our matrix as usual, take the SVD, do the truncated construction of A_1, and use numpy.linalg.norm to look at the norms.

import numpy as np

# Create our matrix A

A = np.array([[3,2,2],[2,3,-2]])

# Take the SVD

U, S, Vh = np.linalg.svd(A)

# Create our rank-1 approximation

sigma1 = S[0]

u1 = U[:, [0]] #shape (2,2)

v1T = Vh[[0], :] #shape (3,3)

A1 = sigma1 * (u1 @ v1T)

# Take norms and view errors

frobenius_error = np.linalg.norm(A - A1, ord="fro") #Frobenius norm

operator_error = np.linalg.norm(A - A1, ord=2) #operator norm

Let's see if we get what we expect.

>>> sigma1

np.float64(4.999999999999999)

>>> u1

array([[-0.70710678],

[-0.70710678]])

>>> v1T

array([[-7.07106781e-01, -7.07106781e-01, -6.47932334e-17]])

>>> A1

array([[2.50000000e+00, 2.50000000e+00, 2.29078674e-16],

[2.50000000e+00, 2.50000000e+00, 2.29078674e-16]])

>>> frobenius_error

np.float64(3.0)

>>> operator_error

np.float64(3.0)

So this numerically confirms the EYM theorem.

Centering data

In data science, we rarely apply low-rank approximation to raw values directly, because translation and units can dominate the geometry. Instead, we apply these methods to centered (and often standardized) data so that low-rank structure reflects relationships among features rather than the absolute location or measurement scale. Centering converts the problem from approximating an affine cloud to approximating a linear one, in direct analogy with including an intercept term in linear regression. Therefore, before we can analyze the variance structure, we must ensure our data is centered, i.e., that each feature has a mean of 0. We achieve this by subtracting the mean of each column from every entry in that column.

Suppose X is our n \times p data matrix, and let

\mu = \frac{1}{n}\mathbb{1}^T X.

Then

\hat{X} = X - \mu \mathbb{1}

will be centered data matrix.

Example. Going back to our housing example, the means of the columns are 1770, 164, 3.2, and 547, respectively. So our centered matrix is

\hat{X} = \begin{bmatrix} -170 & -16 & -0.2 & -47 \\ 330 & 31 & 0.8 & 103 \\ -220 & -20 & -1.2 & -72 \\ -170 & -16 & -0.2 & -57 \\ 230 & 21 & 0.8 & 73 \end{bmatrix}.

Let's do this in python.

import numpy as np

import pandas as pd

# First let us make a dictionary incorporating our data.

# Each entry corresponds to a column (feature of our data)

data = {

'Square ft': [1600, 2100, 1550, 1600, 2000],

'Square m': [148, 195, 144, 148, 185],

'Bedrooms': [3, 4, 2, 3, 4],

'Price': [500, 650, 475, 490, 620]

}

# Create a pandas DataFrame

df = pd.DataFrame(data)

# Create out matrix X

X = df.to_numpy()

# Get our vector of means

X_means = np.mean(X, axis=0)

# Create our centered matrix

X_centered = X - X_means

# Get the SVD for X_centered

U, S, Vh = np.linalg.svd(X_centered)

This returns the following.

>>> X_means

array([1770. , 164. , 3.2, 547. ])

>>> X_centered

array([[-1.70e+02, -1.60e+01, -2.00e-01, -4.70e+01],

[ 3.30e+02, 3.10e+01, 8.00e-01, 1.03e+02],

[-2.20e+02, -2.00e+01, -1.20e+00, -7.20e+01],

[-1.70e+02, -1.60e+01, -2.00e-01, -5.70e+01],

[ 2.30e+02, 2.10e+01, 8.00e-01, 7.30e+01]])

We will apply the low-rank approximations from the previous sections. First let's see what our SVD looks like, and what the condition number is.

>>> U

array([[-0.32486018, -0.81524197, -0.01735449, -0.17188722, 0.4472136 ],

[ 0.63705869, 0.10707263, -0.3450375 , -0.51345964, 0.4472136 ],

[-0.42643013, 0.35553416, -0.61058318, 0.34487822, 0.4472136 ],

[-0.33034709, 0.436448 , 0.61781883, -0.3445052 , 0.4472136 ],

[ 0.44457871, -0.08381281, 0.35515633, 0.68497384, 0.4472136 ]])

>>> S

array([5.44828440e+02, 7.61035608e+00, 8.91429037e-01, 2.41987799e-01])

>>> Vh.T

array([[ 0.95017495, 0.29361033, 0.08182661, 0.06530651],

[ 0.08827897, 0.06690917, -0.71081981, -0.69459714],

[ 0.00276797, -0.04366082, 0.69629997, -0.71641638],

[ 0.29894268, -0.95258064, -0.05662119, 0.00417714]])

>>> np.linalg.cond(X_centered)

np.float64(2251.4707027583063)

Now let's approximate our centered matrix \hat{X} by some lower-rank matrices. First, we'll define a function which will give us a rank k truncated SVD.

# Defining the truncated svd

def reduced_svd_matrix_k(U, S, Vh, k):

Uk = U[:, :k]

Sk = np.diag(S[:k])

Vhk = Vh[:k, :]

return Uk @ Sk @ Vhk

Now, as \hat{X} has rank 4, we can do a reduced matrix of rank 1,2,3. We will do this in a loop.

Remark. We'll divide the error by the (Frobenius) norm so that we have a relative error. E.g., if two houses are within 10k of each other, they are similarly priced. The magnitude of error being large doesn't say much if our quantities are large.

for k in [1, 2, 3]:

# Define our reduced matrix

Xck = reduced_svd_matrix_k(U, S, Vh, k)

# Compute the relative error

rel_err = np.linalg.norm(X_centered - Xck, ord="fro") / np.linalg.norm(X_centered, ord="fro")

# Print the information

print(Xck, "\n", f"k={k}: relative Frobenius reconstruction error on centered data = {rel_err:.4f}", "\n")

And let's see what we get.

[[-168.1743765 -15.62476472 -0.48991109 -52.91078079]

[ 329.79403078 30.64054254 0.96072753 103.7593243 ]

[-220.7553464 -20.50996365 -0.64308544 -69.45373002]

[-171.01485494 -15.88866823 -0.49818573 -53.80444804]

[ 230.15054706 21.38285405 0.67045472 72.40963456]]

k=1: relative Frobenius reconstruction error on centered data = 0.0141

[[-1.69996018e+02 -1.60398881e+01 -2.19027093e-01 -4.70007022e+01]

[ 3.30033282e+02 3.06950642e+01 9.25150039e-01 1.02983104e+02]

[-2.19960913e+02 -2.03289247e+01 -7.61220318e-01 -7.20311670e+01]

[-1.70039621e+02 -1.56664278e+01 -6.43206200e-01 -5.69684681e+01]

[ 2.29963269e+02 2.13401763e+01 6.98303572e-01 7.30172337e+01]]

k=2: relative Frobenius reconstruction error on centered data = 0.0017

[[-1.69997284e+02 -1.60288915e+01 -2.29799059e-01 -4.69998263e+01]

[ 3.30008114e+02 3.09136956e+01 7.10984571e-01 1.03000519e+02]

[-2.20005450e+02 -1.99420315e+01 -1.14021052e+00 -7.20003486e+01]

[-1.69994556e+02 -1.60579058e+01 -2.59724807e-01 -5.69996518e+01]

[ 2.29989175e+02 2.11151332e+01 9.18749820e-01 7.29993076e+01]]

k=3: relative Frobenius reconstruction error on centered data = 0.0004

This seems to check out -- it says that one rank (or one feature) should be roughly enough to describe this data. This should make sense because clearly the square meterage, # of bedrooms, and price depend on the square footage.

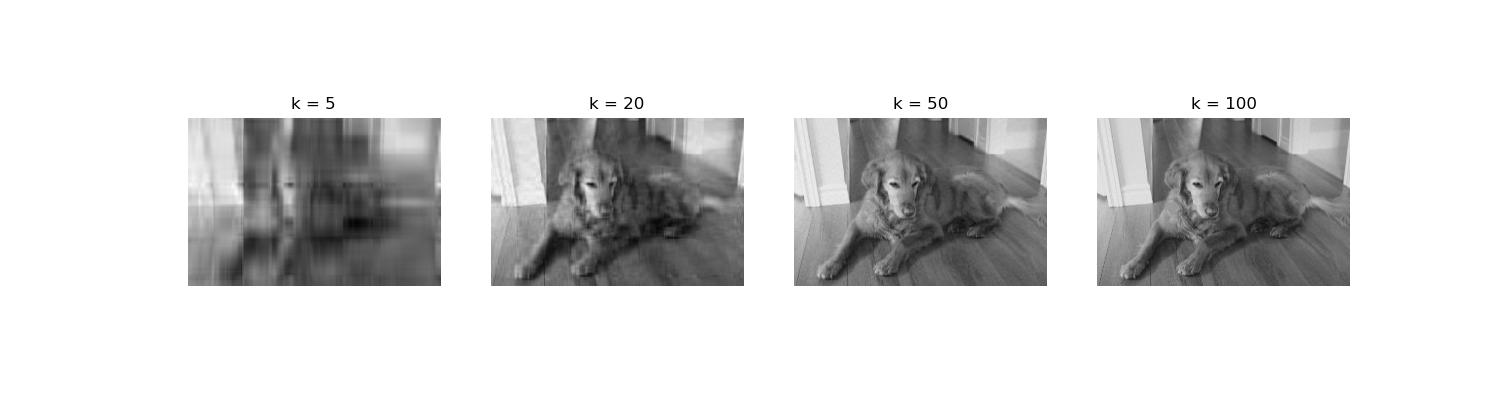

Project: Spectral Image Denoising via Truncated SVD

In this project, we will use Truncated Singular Value Decomposition (SVD) to denoise a grayscale image. The idea is based on the Eckart-Young-Mirsky theorem: the best low-rank approximation of a matrix (in Frobenius norm) is given by truncating its SVD.

Outline.

- Convert an image of my sweet, sweet dog, Bella to a grayscale image.

- Load the grayscale image.

- Add synthetic Gaussian noise to the image.

- Treat the image as a matrix and compute its SVD.

- Truncate the SVD to keep only the top

ksingular values. - Reconstruct the image from the truncated SVD.

- Compare the original, noisy, and denoised images visually and quantitatively.

The Setup: Images as Matrices

Suppose we have a digital image of my dog, Bella. For simplicity, let's assume it is a grayscale image. From the perspective of a computer, this image is simply a large n \times p matrix A, where n is the height in pixels and p is the width. The entry A_{ij} represents the brightness (intensity) of the pixel at row i and column j, typically taking values between 0 (black) and 255 (white) (or 0 and 1 if we normalize). This matrix representation allows us to leverage linear algebra techniques for image manipulation and analysis.

Remark. Color images, by contrast, consist of multiple channels (e.g., RGB), and are therefore naturally represented as collections of matrices. To avoid introducing additional structure unrelated to the core linear algebraic ideas, we will restrict ourselves to grayscale images. That is, we will convert a chosen image into grayscale and apply the SVD directly.

Experimental Setup

We will perform the following steps.

- Load an preprocess the image. Convert the image to grayscale to simplify the analysis.

- Add artificial Gaussian noise. Introduce synthetic Gaussian noise to simulate real-world noise.

- Compute the SVD. Decompose the noisy matrix into its singular values and vectors.

- Truncating the SVD. Retain only the top

ksingular values to create a low-rank approximation. - Reconstructing the Image. Use the truncated SVD to reconstruct the denoised image.

- Comparing results. Visually and quantitatively compare the original, noisy, and denoised images.

Loading and Preprocessing the Image

Let's start with this picture of my beautiful dog Bella. Here it is!

Let's first convert it to grayscale.

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from PIL import Image

# Load image and convert to grayscale

img = Image.open("bella.jpg").convert("L")

A = np.array(img, dtype=float)

plt.imshow(A, cmap="gray")

plt.title("Original Grayscale Image")

plt.axis("off")

plt.show()

Adding Noise

Noise is added to the image to simulate real-world conditions. The noise level can be adjusted to see how the denoising algorithm performs under the difference noise conditions. The noisy image matrix A_{\text{noisy}} is created by adding Gaussian noise to the original matrix A.

rng = np.random.default_rng(0)

noise_level = 25

A_noisy = A + noise_level * rng.standard_normal(A.shape)

plt.imshow(A_noisy, cmap="gray")

plt.title("Noisy Image")

plt.axis("off")

This gives the following image.

SVD

Recall that the SVD of A is given by A = U\Sigma V^T where U is an n \times n orthogonal matrix, V is a p \times p orthogonal matrix, and \Sigma is an n \times p diagonal matrix with the singular values on the diagonal, in decreasing order. The left singular vectors correspond to the principal components of the image columns, while the right singular vectors correspond to the principal components of the image rows.

The truncated SVD is given by A_k = U_k\Sigma_kV_k^T, where U_k,V_k, \Sigma_k are the truncated versions of U,V, \Sigma, respectively. This truncated SVD gives a best approximation of our matrix by a lower rank matrix, in terms of the Frobenius norm. Truncating the SVD is equivalent to projecting the image onto the top k principal components.

The larger singular values correspond to the most important features of the image, while the smaller singular values often contain noise. By truncating the smaller singular values, we can remove the noise while preserving the essential information.

# Take the SVD

U, S, Vh = np.linalg.svd(A_noisy)

# Define the truncated SVD

def truncated_svd(U, S, Vh, k):

return U[:, :k] @ np.diag(S[:k]) @ Vh[:k, :]

If you run the code, you'll see that it takes a bit. This is because computing the SVD of a large image is computationally expensive. There are other methods (e.g., randomized SVD) that exist for scalability.

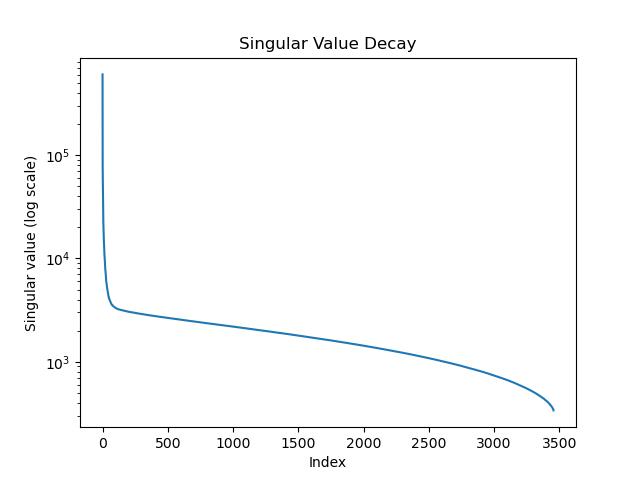

Singular Value Decay

As mentioned, the singular values of an image typically decay rapidly, with the largest singular values capturing most of the important information. The smaller singular values often contain components with noise. We plot the singular values on a log scale, we can determine an appropriate truncation point k.

plt.semilogy(S)

plt.title("Singular Value Decay")

plt.xlabel("Index")

plt.ylabel("Singular value (log scale)")

plt.show()

Reconstructing the image

We reconstruct our image precisely from the truncated SVD A_k = U_k\Sigma_k V_k^T.

import math

# Choose values of $k$

ks = [5, 20, 50, 100]

n_images = len(ks) # total number of reconstructions

n_cols = 2 # number of columns in the grid

n_rows = math.ceil(n_images / n_cols)

# Create the grid of subplots

fig, axes = plt.subplots(